However, the proprietary nature will gradually disappear as several state governments have initiated mapping farm-specific data and intend to make it available to users at large with a transparent access policy. In India, agricultural data is a difficult market, given that most agricultural holdings are small, and the states will necessarily engage in pursuing large-scale surveys with the inevitable engagement of the government to provide benefits to smallholder farmers.

We are optimistic about farmers securing quality data relating to critical elements determining farm input and crop care from multiple sources. The competing players will deliver the services pro-bono or at negligible cost to the farmers, making independent service providers continuously search for a steady customer base. The indefinite time to accomplish unit economics will force ventures to seek overwhelming capital in successive doses. Some have ventured to offer services in more developed markets such as Europe to gain a revenue base.

Needless to say, there is competition in these markets from agri product companies, and the sustainability of such operations in these markets would require even higher capital mobilization. The impact perceived in delivering services to smallholder farmers does not arise in such competing services provided in mature European markets, and sustainability in such markets will depend on competitive unit economics for services offered. The international revenues for Indian companies providing services in such a market are minuscule. A common concern expressed by some of the farmers and farm clusters relates to the data privacy and data ownership for farmland-related data captured by service providers. There are currently less structured agreements and, in many cases, no agreement with farmers on data ownership and usage. The interoperability of the data is a challenge, too, as companies have piled data in non-standard formats and platforms, retaining them as proprietary information.

Our interactions with farmers indicate their perception of the advisory provided as devoid of scientific merit, making them less reliable on the advisory. The lack of credible, unbiased scientific research-based advisory that they secure from agriculture universities in their region is relied upon by them rather than generic solutions provided by service providers as they look for specific crop solutions that are unforeseen in successive seasons (such as the emergence of Western Flower thrips in Pepper in the last season).

The service providers currently depend on imported hardware such as sensors mainly from

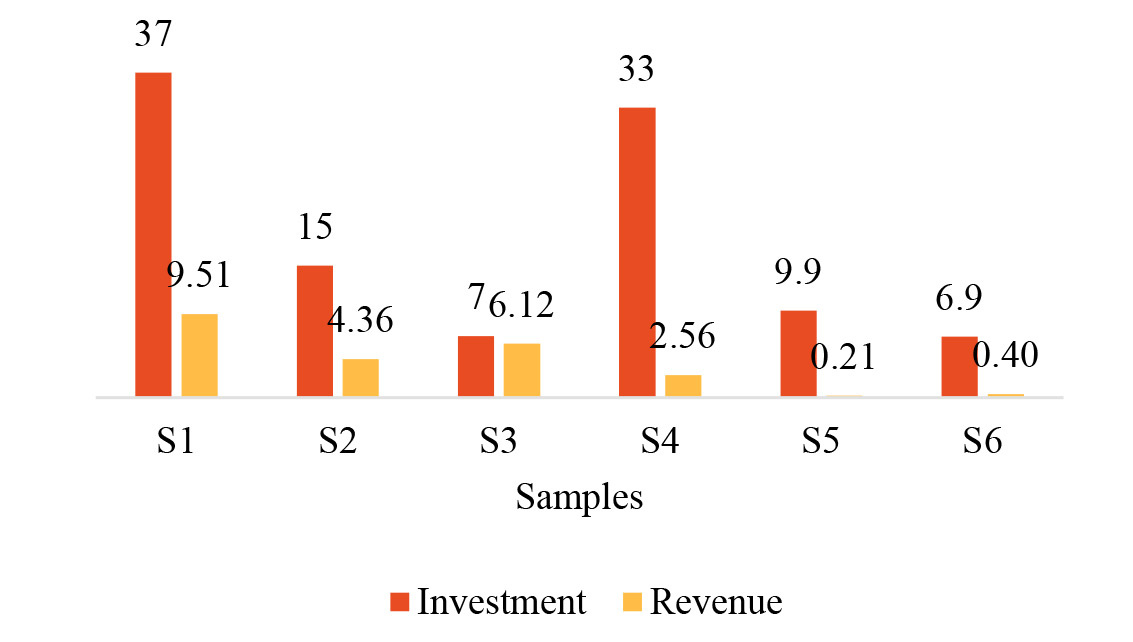

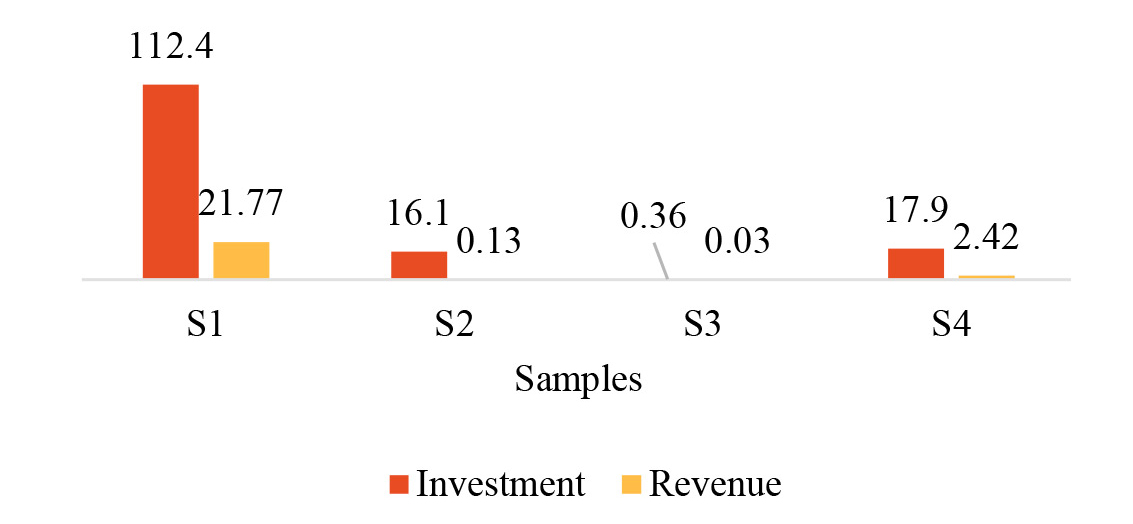

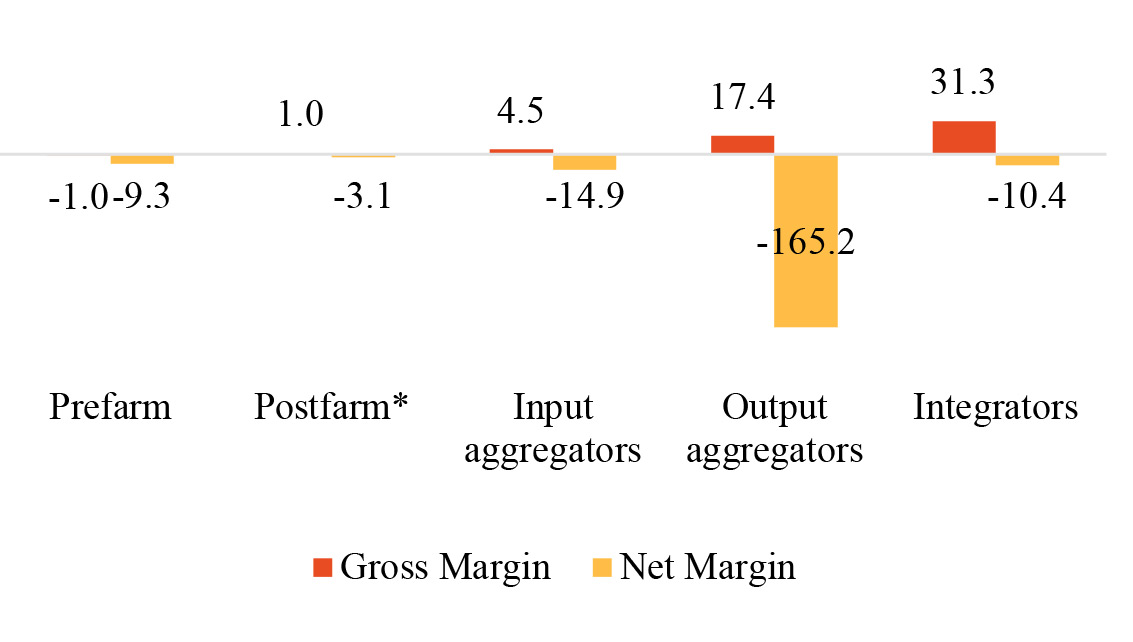

China, and the cost of hardware is a deterrent for pro-bono services. The adoption of drones will widen in India with government-driven initiatives for indigenous production and more profound efforts from state governments to provide access to drones for smallholder farmers. However,they may not offer a distinct advantage for independent service providers. A review of the performance of the top four entities in the segments reflects that the largest among them has accomplished revenue during the last year at 10% of total funds mobilized in three successive rounds.

The loss before interest was twice that of gross revenue from services, reflecting a long pathway to attain break-even revenues from services. Since spread to a larger number of farmers will result in higher losses due to unfavorable unit economics, their losses will grow higher as these entities grow more extensive in their reach to farmers.